Here is the Answer Key for your Grammar 4Level

Category Archives: Grammar, Usage, Mechanics

National Punctuation Day

“The Secret Emotional Lives of 5 Punctuation Marks”

By: Arika Okrent

1. THE ANGRY PERIOD

What could be simpler than period? One little dot that ends a sentence, a few pixels. But lately, the period has become a bit more than that. As Ben Crair noted at The New Republic, when it comes to online chatting and texting, the period has come to mean “I am not happy about the sentence I just concluded.” Since digital communication is more like an ongoing conversation, people usually leave off final punctuation and just hit send. In that context, a period starts to look a little abrupt and aggressive. A study by Idibon adds support to the idea of the negative period . . .

2. THE SINCERE EXCLAMATION POINT

The exclamation point has long been seen as a marker of loudness or excitement, but its emotional range is more complex than that. In digital communication it has become a sincerity marker. In an email, where it might seem a little too informal to just leave off end punctuation, the exclamation point serves as a solution to the problem of the angry period. This comes off dry, cold, and little sarcastic: “I am looking forward to the meeting.” But with the exclamation point—“I am looking forward to the meeting!”—it is warm and sincere. It adds not a shout, but a genuine smile.

3. THE COY, AWKWARD ELLIPSIS

The ellipsis, a row of three dots, stands for an omitted section of text. But much can be conveyed by omission. It asks the receiver of the message to fill in the text, and in that way is very coy and potentially flirty. “Pizza…” Is that an invitation? An opinion? It sits there waiting for a response. This brings awkwardness into the equation, and the ellipsis (or even the written words “dot dot dot”) is another way to say “well this is awkward.” The conversation is not over, but someone has to make a move. And the clock ticks uncomfortably on, dot…by dot…by dot…

4. THE DRAMATIC ASTERISK

Asterisks are meant to be noticed. They hold a place in a text for you so you can go match it up with a footnote or comment. But they also have a theatrical bent that goes beyond simple attention holding and crosses over into acting. As discussed by Ben Zimmer in this Language Log post, asterisks (*ahem*) can set off stage directions (*cough*) that tell you (*looks at watch*) about the emotional states (*yawn*) and attitudes (*stares off*)…sorry, (*vigorously blinks eyes*) where was I? Asterisks. They’re little jazz hands that say, “look what I’m doing!”

5. THE DULL COMMA

Commas have no inner emotional lives. In the words of Gertrude Stein, “commas are servile and they have no life of their own.” Not only that, their dullness can rub off on you. A comma “by helping you along holding your coat for you and putting on your shoes keeps you from living your life as actively as you should lead it.” That may sound mean, but the comma really doesn’t care. In order to get out there every day to step between words and generally slow things down, it’s got to have a businesslike attitude.

(Source: mentalfloss.com)

On Writing…

As a teacher, I’ve relied the most on two books: Eudora Welty’s One Writer’s Beginnings and Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. I’m posting excerpts from an interview with King wherein he shares his thoughts on teaching writing to teen-agers (middle-schoolers).

Lahey: If your writing had not panned out, do you think you would have continued teaching?

King: Yes, but I would have gotten a degree in elementary ed. I was discussing that with my wife just before I broke through with Carrie. Here’s the flat, sad truth: By the time they get to high school, a lot of these kids have already closed their minds to what we love. I wanted to get to them while they were still wide open. Teenagers are wonderful, beautiful freethinkers at the best of times. At the worst, it’s like beating your fists on a brick wall. Also, they’re so preoccupied with their hormones it’s often hard to get their attention.

Lahey: You write, “One either absorbs the grammatical principles of one’s native language in conversation and in reading or one does not.” If this is true, why teach grammar in school at all? Why bother to name the parts?

King: When we name the parts, we take away the mystery and turn writing into a problem that can be solved. I used to tell them that if you could put together a model car or assemble a piece of furniture from directions, you could write a sentence. Reading is the key, though. A kid who grows up hearing “It don’t matter to me” can only learn doesn’t if he/she reads it over and over again.

Lahey: In the introduction to Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, E.B. White recounts William Strunk’s instruction to “omit needless words.” While your books are voluminous, your writing remains concise. How do you decide which words are unnecessary and which words are required for the telling?

King: It’s what you hear in your head, but it’s never right the first time. So you have to rewrite it and revise it. My rule of thumb is that a short story of 3,000 words should be rewritten down to 2,500. It’s not always true, but mostly it is. You need to take out the stuff that’s just sitting there and doing nothing. No slackers allowed! All meat, no filler!

Lahey: By extension, how can writing teachers help students recognize which words are required in their own writing?

King: Always ask the student writer, “What do you want to say?” Every sentence that answers that question is part of the essay or story. Every sentence that does not needs to go. I don’t think it’s the words per se, it’s the sentences. I used to give them a choice, sometimes: either write 400 words on “My Mother is Horrible” or “My Mother is Wonderful.” Make every sentence about your choice. That means leaving your dad and your snotty little brother out of it.

Lahey: Great writing often resides in the sweet spot between grammatical mastery and the careful bending of rules. How do you know when students are ready to start bending? When should a teacher put away his red pen and let those modifiers dangle?

King: I think you have to make sure they know what they’re doing with those danglers, those fragmentary and run-on sentences, those sudden digressions. If you can get a satisfactory answer to “Why did you write it this way?” they’re fine. And—come on, Teach—you know when it’s on purpose, don’t you? Fess up to your Uncle Stevie!

(Source: “How Stephen King Teaches Writing”, The Atlantic)

March Forth – National Grammar Day

Ten Grammar Myths Exposed

- A run-on sentence is a really long sentence.

- You shouldn’t start a sentence with the word “however.”

- “Irregardless” is not a word.

- There is only one way to write the possessive form of a word that ends in “s.”

- Passive voice is always wrong.

- “I.e.” and “e.g.” mean the same thing.

- You use “a” before words that start with consonants and “an” before words that start with vowels.

- It’s incorrect to answer the question “How are you?” with the statement “I’m good.”

- You shouldn’t split infinitives.

- You shouldn’t end a sentence with a preposition.

Brief explanations with links to more detailed discussions

Pronouns Study (Review)

This is an intensive, self-paced multi-week review that should be completed before February 21. Each step of this review will give you an idea of your progress that will determine how much time you will need to devote to your learning.

- In your Grammar Notebook, using only your memory, create a Frayer Model for Pronouns: Definition, Characteristics/Illustration, Examples, & Non-examples.

- When you’ve done all the you can with the FM, refer to your SpringBoard and your previous grammar notes to fill in any gaps (use a different color pen).

- Log-in to a computer/tablet and go to the Grammar tab on the blog

- “Play” with grammar using the following resources: “GrammarBytes” (on the blog); “Grammar Pop” (not free); or “Quiz Up” (free).

- Access: http://www.grammar-monster.com/lessons/pronouns.htm to learn more about Pronouns and create various pronouns charts/tables in your Grammar Notebook. You can search pronouns and click on “images” to see the kinds of charts/tables you can create to help you.

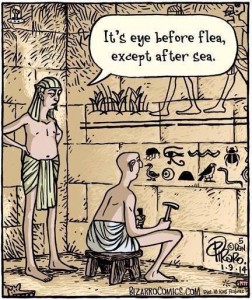

Early Grammar Police

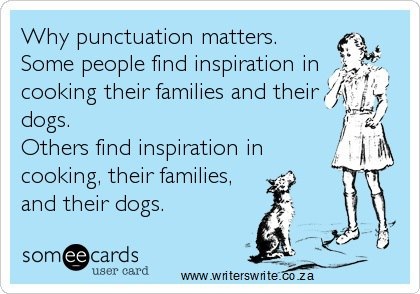

Why Punctuation Matters

AWUBIS – IW Revisions

Adding another layer to revising sentences:

Revise each sentence by using a subordinating conjunction (AWUBIS) at the beginning of each sentence. This will cause you to be deliberate and think about your subject adn predicate. This exercise will cause you to be aware of the flow and lucidity of your writing.

Follow this order:

1-A

2-W

3-U

4-U

5-B

6-I

7-S

If you have more than 7 sentences, begin again with “A”.

Q3/IW3 – Sentence Revisions

Procedures:

- Title your assignment as you would any IW day.

- Choose the IW that you want to revisit to revise from start to finish. Choose one that has 5-7 sentences.

- Write the title of the IW that you will revise on your notebook paper (For example: Q1/IW3)

- Number the sentences in the original IW.

7th Grade: Sentence Revision Directions:

1. Write the original sentence.

2. Identify the parts of sentence above the word(s). — Level 2

3. Identify the phrases with ( ). — Level 3

4. Identify the clauses by underlining IC & putting brackets around [ DC]. — Level 4

6th Grade: Sentence Revision Directions:

1. Write the original sentence.

2. Identify the parts of sentence above the word(s). — Level 2

3. Identify the prepositional phrases with ( ).

4. Revise the original sentence so that the subject and predicate are clear. Use the Active voice verb tense as much as possible. Make sure that your DOs, IOs, and SCs are clear. Use Nouns and verbs that are “powerful”.

S LVP SC-PA SC-PA

S1: The kids are tall and skinny, (with glasses.)

R1:

S2:

R2:

Good to Great Sentences

A mentor of mine once told me, “If you’re not getting better, you’re getting worse.” This stems from our having studied and implemented the philosophy of Jim Collins’ book Good to Great. I’m always looking for ways to make improving yourself and your learning better or more meaningful, so I’ve come up with “Good to Great” Sentences.

“Good to Great” Sentences

Learning Targets: I can…

…create good, solid foundation sentences that contain the following parts:

Subject – Action Verb Predicate – (Indirect Object) – Direct Object – (Object Complement)

Subject – Linking Verb Predicate – Subject Complement (Predicate Nominative

or Predicate Adjective).

…enhance and manipulate syntax and maintain clarity when I incorporate phrases and clauses.

Foundation Sentence #1: S – AVP – (IO) – DO – (OC)

L2: Create or rewrite a L2 sentence from previous writing assignments. Incorporate and be deliberate about the nouns and verbs (and adjectives) that you use. Focus on using powerful nouns and verbs before using vivid adjectives.

L3/4: Enhance and/or manipulate your L2 sentence by incorporating phrases and clauses. Be sure to maintain clarity.

Foundation Sentence #2: S – LVP – SC (PN or PA)

L2: Create or rewrite a L2 sentence from previous writing assignments. Incorporate and be deliberate about the nouns and verbs (and adjectives) that you use. Focus on using powerful nouns and appropriate verbs before using vivid adjectives.

L3: Enhance and/or manipulate your L2 sentence by incorporating phrases and clauses. Be sure to maintain clarity.